At the height of the Cold War, the strategic reconnaissance aircraft was a convenient piece of equipment. In the days before spy satellites and drones, one of the only ways to know what your enemy was doing was to fly over and have a look.

But doing so was extremely dangerous. Several branches of the US government operated spy planes, including the Air Force and the Central Intelligence Agency. The first mission-designed and highly-successful plane was the U-2 Dragon Lady. But this plane proved vulnerable, even with its ability to fly at altitudes above 70,000 feet.

On these critical missions, speed was of the essence as well. The U-2 was not a fast airplane, so the CIA’s dream for its replacement was an aircraft with stealth capabilities that could fly at extreme altitudes. Dubbed Project Oxcart, the CIA had the A-12 designed. That airframe eventually morphed into the SR-71 Blackbird.

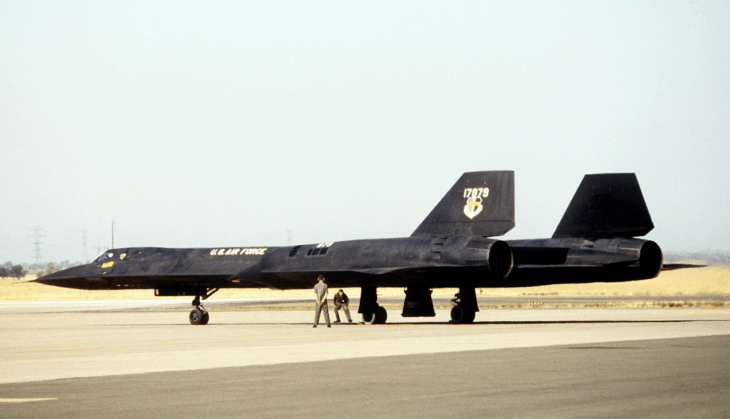

Designed over half a century ago, the SR-71 still holds records as the fastest and highest-flying crewed aircraft. The design pioneered stealth technology. The plane is one of the most distinctive and storied chapters in aviation history.

Purpose and Design

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Cold war between the Soviet Union and the United States was heating up. One of the US’s most valuable assets to keep tabs on their adversary was the U-2 spy plane. The plane flew extraordinarily high and was able to perform reconnaissance deep inside Soviet airspace.

First flown in 1955, the Lockheed U-2 Dragon Lady was an extremely successful spy plane. It wasn’t very fast, with a top speed of around Mach 0.7, but it could get above 70,000 feet. This was high enough to be considered out of the reach of the Soviet air defenses.

Both the Air Force and the CIA operated the U-2 during the Cold War. In 1960, U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers was shot down over Russia by a surface-to-air missile. He survived the incident and was held prisoner by the Soviets, who also recovered many of the plane’s surveillance tools.

Back in the US, there was sudden political will for an even more capable reconnaissance aircraft to be designed, and quickly. The design goals were simple—the new plane needed to be undetectable, and the Russians must be unable to shoot it down. The goal was to fly higher and faster, as much as three times the speed of sound.

The replacement to the U-2 was already in the works, so the design was in place. But the Powers incident greased the wheels in Washington, and the project faced little resistance and open wallets.

Lockheed Skunk Works

The same people who created the U-2 got to work on making an even better plane. That team worked at Lockheed’s Advanced Development Programs, known as Skunk Works. This same lab had produced the WWII-era P-38 Lightning and P-80 Shooting Star, as well as the U-2. Later designs included the F-117 Stealth Fighter and the B-2 Spirit bomber.

Lockheed’s Skunk Works department was known for creating successful cutting-edge designs, usually under the veil of complete secrecy. In the case of the U-2, they even came out on time and under budget. This was a key reason that Skunk Works was chosen to build the next-generation spy plane.

The CIA’s code-name for their next spy plane was Project Oxcart. Preliminary designs for the U-2 had been given “Angel” designations, so it followed that prototype designs for the next would be “Archangels.” The twelfth design, or A-12, was the winner. Less than six months before Powers’ plane was lost over the Soviet Union, the CIA had already ordered twelve A-12 spy planes.

The Air Force briefly played with the idea of turning the A-12 airframe into a bomber, which would be dubbed the B-71. That idea morphed into creating their own reconnaissance/surveillance plane, the RS-71. That name eventually morphed into SR-71 Blackbird, which is said to have meant “strategic reconnaissance.” The airframe was also used to create the YF-12, a supersonic fighter/interceptor.

Blackbird Variants — A-12, YF-12, and SR-71

Lockheed A-12

The A-12 was the predecessor to the SR-71. It was ordered from Lockheed Skunk Works in the late 1950s by the Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA wanted a plane with a super low radar profile, and so many revisions of the design were rejected before approval of the A-12.

The A-12 performed its test flights under top-secret conditions at Groom Lake, Nevada, the area known as “Area 51.” The first flights didn’t go quite as planned.

Lockheed had a tradition of flying their planes briefly before the official maiden flight to ensure everything functioned as designed. It helped the company save face and reduced the possibility of nasty surprises in the days before computer design and simulation.

During that first flight, the airframe had such poor control that the test pilot opted to land two miles straight ahead on a dry lake bed. Turning back to the runway was too big a risk. As it turned out, some navigational controls were hooked up improperly, and the problem was rectified by the next day.

The official test flight occurred the following day on April 27, 1962. The landing gear was left extended, just in case. Bits of metal flew off the wings, but the plane returned for a safe landing, and the chief designer was overall pleased with how it went. Technicians spent days searching the desert to find all of the pieces.

The A-12 program continued many years, with 13 planes built. The A-12 was a single-crew plane that carried photographic surveillance equipment. Only one plane had two seats, and this was a variant used for training. The pilots called it the “Titanium Goose.”

A few months after the successful test flights, the USAF approached Skunk Works about using the airframe for their reconnaissance missions and as a fighter/interceptor. The projects were designated the SR-71 and the YF-12, respectively.

Lockheed YF-12 Air Force Fighter / Interceptor

The first YF-12 first flew in 1963, and the SR-71 flew in December of 1964. The YF-12 never made it to active duty, and only three aircraft were built. The design never received the funding needed to get it into operational use.

Interestingly enough, the existence of the YF-12 prototype was revealed to the public during the presidential campaign of 1964. Challenger Barry Goldwater criticized the incumbent Lyndon B. Johnson for not developing new military technologies and letting the US fall behind in the Cold War. Johnson decided to reveal the existence of the YF-12, which was politically convenient. The project got canceled anyway, and its existence provided a cover story to hide the existence of the CIA’s still top secret A-12.

Both the YF-12 and the later SR-71 Blackbird were slightly larger and heavier than the A-12. They each carried different payloads, mission-specific for the tasks at hand. The result was that each of the three variants had different performance numbers, but the design got better with each revision.

The nose of the YF-12 was heavily modified to accommodate the large Hughes AN/ASG-18 fire control radar for the air-to-air missile system. The changes to the chine required the additions of ventral fins to maintain directional control.

Lockheed M-12 Mothership and D-21 Drone

The M-12 was designed to carry a drone on top. This drone looked like a smaller version of the A-12 and was designated the D-21. The D-21 flew deeper into enemy territory, higher and faster than even the M-12 could. It then flew back to a safe area, jettisoned its reconnaissance package, and then self-destructed. The information package it collected was picked up mid-air by a C-130 cargo plane.

The Lockheed D-21 drone could fly at over Mach 3.3 and at altitudes above 90,000 feet.

The M-12 program was abandoned after a mishap when launching the drone, resulting in the loss of an M-12. The D-21 drone remained in use, launched from conventional bombers, but it wasn’t very successful. Only two M-12s were built. The remaining plane is on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle.

Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird

The last variant to be built and designed benefitted from the trial and error began several years before. The SR-71 shared some of the modifications that the YF-12 had, mainly its larger size and weight. It also carried a crew of two. But the aircraft retained its original mission to be a high-speed and high-flying spy plane.

A total of 32 Blackbirds were built, and they were in service for 34 years. In addition to the Air Force, NASA operated a few at their Dryden Research Laboratory.

A-12 versus SR-71

While the airframe variants were very similar, they had been modified to carry different surveillance packages. In November 1967, the A-12 and the SR-71 went head-to-head in a reconnaissance fly-off over the Mississippi River, code-named Nice Girl.

The planes flew over the same route an hour apart, and the results were carefully studied. The results were inconclusive. The A-12’s camera had a wider field of view, but the SR-71 had some sensors that the A-12 didn’t. The planes’ range turned out to be about the same since the SR-71 carried more fuel but also weighed more. Both planes had tiny radar signatures.

The most significant difference between the designs were the cameras they were designed to carry. The A-12 could use one of three different camera systems, each with a different resolution depending on the mission at hand. The best one covered a 63 nautical mile wide field of view with a resolution of one foot (.3 meters).

The camera on the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird also had the same one-foot resolution but was taken in two separate five-mile wide swaths on each side of the aircraft. The SR-71 had the added capacity for ELINT or electronic signals intelligence. It could pick up transmissions and record them for later deciphering.

Design and Technological Challenges

The design goals for the A-12/SR-71 programs were straight forward, at least at first glance. The desire was to replace the U-2 with a plane that could fly higher and faster. The CIA wanted the plane to be undetectable on the Soviet’s radars. Specifically, the plane was desired to have a 2,000 nautical mile range and be capable of sustained speeds over Mach 3.0. The higher it could fly, the better. Higher altitudes meant less chance of detection, and they meant less danger from surface-to-air missiles (SAMs).

Designing a plane for sustained operation at these speeds required special considerations. Luckily, the team at Skunk Works, led by chief engineer Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, was the best of the best. That team successfully produced an aircraft that met all of its expectations and lives on today as the fastest manned aircraft ever produced.

Russian Titanium

The heat generated by airflow over the skin of the aircraft would melt traditional aluminum airplanes. A titanium alloy, which provided exceptional strength and heat resistance, was used in 85 percent of the airframe.

Ironically, titanium was in short supply during the Cold War. The US has few titanium resources; the only place on earth where large amounts are found are within the Soviet Union. To procure enough titanium to build the planes, the CIA worked undercover, forming bogus companies in Third World countries to procure it.

Another challenge came from working with the titanium. The metal is so strong that conventional machining processes had to be retooled.

Leaking Fuel

Even with titanium, the heat caused major expansion during flight. The surface had to have a corrugated texture, which allowed the metal to expand vertically and horizontally. Had it been smooth, the metal would’ve split or curled. Since the metal expanded so much during flight, the panels that made up the outer skin were loose-fitting when cool. The gaps were so significant that jet fuel leaked out of the plane when it was fueled before takeoff.

Quartz Windscreen

Simple things, like the windscreen, needed to be designed from scratch because of the extreme operating environment. The windshield was made of quartz and was ultrasonically welded to a titanium frame since standard adhesion methods would just melt—the windscreen reached temperatures as much as 600 degrees Fahrenheit.

Special Tires

Even the tires on the Blackbird were special. They were filled with nitrogen and custom made by BF Goodrich. At $2,300 per tire, each one lasted only 20 missions. Landing speed for the plane was a whooping 170 knots, so a drag chute was used to reduce stress on the tires and brakes.

No Fuel Tank

Instead of fuel tanks, the plane circulated its fuel underneath the outer skin to help cool itself. The cockpit was equipped with a heat exchanger to shed heat away from the pilot and recon officer.

Fuel was a top concern for designers. If the plane’s leading edges got to over 600 degrees Fahrenheit on regular flights, fuel in inner tanks would get to around 375 degrees. To reduce the possibility of an explosion, a unique mix of jet fuel with a very high flashpoint was created. It was known as JP-7. It’s been rumored that you could extinguish a cigarette in a bucket of JP-7 without igniting it.

Difficult Cold Starts

But having a fuel with such a high flashpoint made cold-starting the engines difficult, if not impossible. Johnson and his team created an injection system that used triethyl borane (TEB for short). TEB is extremely explosive, so injecting a small amount in the engine was more than enough to get it running on the JP-7. The TEB was also used to light the afterburners. Each engine had 16 shots of TEB on board.

Special Air Inlets

The engines also had to have special inlets to control airflow. The distinctive spikes on the engine nacelles moved in and out to control the amount of air entering the engine. The spikes kept supersonic airflow from damaging the engines. The conventional turbines became ineffective above Mach 2.5, at which point only the afterburners could continue accelerating the plane. The engine effectively became ramjets at high speeds.

Limited By Temperature

At speeds above Mach 3, the engines were limited by temperature more than anything else. The air coming into the engine was already so hot that fuel and power had to be reduced to keep the engine within its temperature limits. Engine thrust then came mostly from afterburner temperature rise, with the actual turbines producing nothing but drag. This was the limiting factor in the speeds achieved by the Blackbird—the airframe showed no signs of being near its operational limits. But the engine intake air couldn’t go above 800 degrees Fahrenheit without damaging the turbines.

Flying at such high speeds rendered every other available navigation technique obsolete. At such speeds, the Blackbird would cover an area of over 84 nautical miles to make a turn. Northrop modified a missile guidance system for the SR-71 that used celestial navigation to augment a conventional inertial navigation system (INS). This astro-inertial guidance system (ANS) could track stars during both the day and night through a special quartz window behind the cockpit. Of course, the system was called “R2-D2” by the pilots.

A Servicing Nightmare

The SR-71 entered operational service with the 4200th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing at Beale Air Force Base in California in 1966. Each plane could only fly about once a week since they required so much work to turn them around after each flight. The intense heat often resulted in planes returning missing rivets or with fuselage panels delaminated. Sometimes it could take weeks to get a plane ready to fly again.

A typical flight began with a partial fuel load to reduce the stress on the landing gear. The plane then refueled mid-air shortly after takeoff. Air-to-air refueling was a constant during Blackbird missions since the plane had a relatively limited range at supersonic speeds.

The SR-71 required modifications to the KC-135 tanker aircraft to accommodate it. A unique fueling boom needed to be added that allowed the tanker to fly at its maximum speed without any flutter. To maintain flight balance, the tanker had to move around its conventional JP-4 jet fuel and the SR-71’s special JP-7.

Deployment in Vietnam

Even though the plane had been ordered with eyes on Soviet overflights, those flights were not happening by the time it was in service. President Kennedy publicly stated that the US would not engage in overflights, and satellites were doing the job just fine anyway.

The SR-71 was used extensively over North Vietnam and Laos in the late 1960s. They operated from Kadena Air Base in Japan, and their operations were code-named “Black Shield.” Over 800 missiles were launched at SR-71s by the Vietnamese, not a single one ever scoring a hit. The standard defense technique used by the pilots was to speed up. No surface-to-air missile could keep up with the Blackbird.

The Blackbird was also flown on active missions from Mildenhall, England, to monitor the Soviet’s northern navy.

The Blackbird was phased out of active service in 1989, although it was briefly reactivated in the 1990s. The plane’s mission had largely been replaced by high-resolution reconnaissance satellites, making the costly plane unnecessary. For those missions requiring rapid overflights, unmanned drones are now widely used.

Much of what we know about the Blackbird has only recently become declassified. You can even find the declassified Flight Manual online now.

World Records Held

The SR-71 shattered speed and altitude records throughout its venerable career. For air-breathing operational crewed aircraft, the SR-71 is still the fastest (Mach 3.3, 1,905.81 knots, 2,193.2 mph, 3,529.6 km/h), and the highest-flying (85,069 feet).

On several occasions, pilots indicated that they’d flown faster than the record-setting Mach 3.3. One pilot stated that he flew “in excess of Mach 3.5” when evading a missile over Libya.

The SR-71 also holds speed records over recognized courses. Here are just a few examples.

- New York to London, 3,461.53 miles, 1,806.964 mph, 1 hour 54 minutes 56.4 seconds

- Los Angeles to Washington DC, 2,299.7 miles, 2,144.8 mph, 64 minutes 20 seconds

- St Louis, MO to Cincinnati, OH, 311.4 miles, 2,189.9 mph, 8 minutes 32 seconds

The plane won the Mackay Trophy in 1971 for the most meritorious flight of the year for completing 15,000 miles in ten and a half hours. In 1972 it won the Harmon Trophy for most outstanding international achievement in aeronautics.

SR-71 Replacement

During the 1980s, there was great speculation about the next big project to come out of Skunk Works to replace the SR-71. The rumored project, supposedly code-named Aurora, was never confirmed. Many aviation observers believed that the US must be developing some Mach 5+ hypersonic replacement for the SR-71. A former head of Skunk Works wrote that the B-2 stealth bomber program was code-named “Aurora,” and that that’s how it all got started.

Regardless, there has never been any conclusive evidence that Aurora existed. Many sonic boom and possible sightings occurred in the early 1990s, but they dropped off significantly. That could indicate that the program was just a hypersonic prototype or possibly an active project that got defunded.

The Lockheed SR-72, or the “Son of Blackbird,” was proposed in 2013. The design supposedly can fly at Mach 6 and is roughly the size of the Blackbird. Various statements in Lockheed press releases have hinted that the aircraft has been in the design phase and could be flown sometime in the 2020s.

Much research and time have gone into developing the high-speed engine technologies such an aircraft would need, including ramjets and scramjets. If such an aircraft does exist, the SR-71s speed records may still stand. Any new design is likely to be an unmanned vehicle.

Checkout more photos and details about the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird in our aircraft archive.

Related Posts